When J.R.R. Tolkien published The Hobbit in 1937 it was the intention of the publishers was to market the work as a new fairytale for children; part of that marketing included decorating the book with full-paged illustrations to add to its charm. This is why so many editions of The Hobbit come so stylized today, because in essence it’s marketed for young readers, just as The Lord of the Rings is supposed to be marketed toward the grown-up versions of those readers.

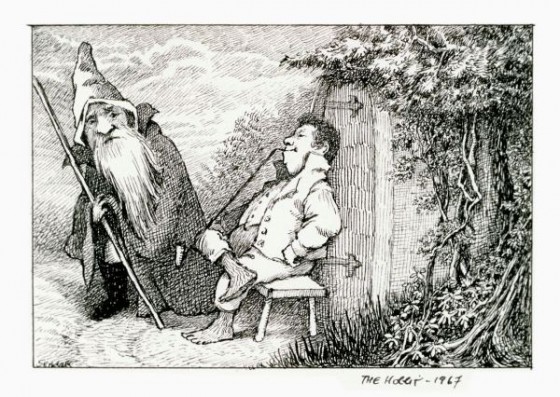

When fascination with Middle Earth got its second wind in the 60’s the publishers approached Maurice Sendak, author and illustrator of Where the Wild Things Are to reimagine The Hobbit for it’s 30th anniversary publication. Sendak produced two illustrations to be submitted to Tolkien for approval. The first is the image you see above, depicting Bilbo enjoying a pipe on his porch while Gandalf looks on. The second was of wood-elves dancing in the moonlight, and has been lost to us since its creation.

Though Tolkien was 75 by the time the 30th anniversary of The Hobbit was getting ready to print, he was still very much involved with his literary empire. It turns out that editor mislabeled Sendak’s work and identified the wood-elves as hobbits, which annoyed Tolkien. He accused Sendak of not reading the book closely enough and the deal was off.

While the publisher tried to smooth things over between the two, Sendak had his first heart attack the day before they were to meet and sort out the misunderstanding. He never met with Tolkien and the project never came to be.

[The Shakedown]

It’s odd how things work out. Had one incompetent editor not dropped the ball, my collector’s edition of The Hobbit could feature artistic interpretations by Maurice Sendak. The image above is absolutely is stunning in it’s simplicity and it’s subtext. Sendak had a way of subtly capturing the essence of characters and telling their stories without words. Look at Gandalf. His sad eyes, his slightly hunched posture, and the heavy cross-hatching used in his coloring are all intentional devices used to speak to the reader. He’s ancient, weary, and has seen so much both good and bad. Contrast him to Bilbo who, at the beginning of The Hobbit, is almost as innocent as a child. His depiction is light, and whimsical, capturing his inner spirit.

It’s sad that I’ll never get to share a book of such images with my child as I read to him or her the story of Middle Earth. But at the same time, I’m grateful for the legacy Tolkien has given the world. Not only in the work he has done, but in the inspiration he has given others. I’ve seen a lot of artistic interpretations inspired by The Lord of the Rings, so far and I’m excited to see what Peter Jackson has in store for us with The Hobbit.

Here’s to a lifetime of artists sharing their own visions of Middle Earth.

Cheers.

[Source] Hero Complex